Programme

We hold winter lectures on industrial archaeology and local history from society members and guest speakers and organise summer visits to local attractions.

Membership

Why not join the S.I.A.S. and enjoy the challenge of discovering the past? You will also be making a contribution to knowledge in the county for future generations.

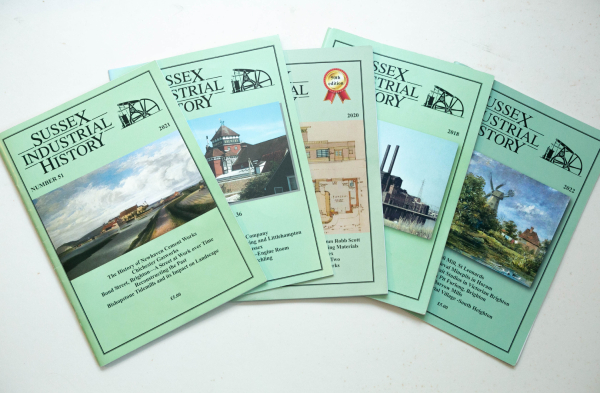

Publications

We publish quarterly newsletters for both SIAS and the Mills Group, an annual journal Sussex Industrial History and books including Brickmaking in Sussex.

What We Do

Industrial archaeology covers a wide variety of topics, including raw materials and their processing, manufacturing, canals, roads railways, utilities, gas water and electricity and all their associated buildings and structures.

We campaign to save historic buildings and structures of IA interest from demolition or unsuitable conversion and have been successful in getting some important buildings listed.

SIAS has a Mills Group dedicated to the study of wind and water mills in the county, and membership of SIAS includes the Sussex Mills Group

SIAS is affiliated to Amberley Museum, the museum of the South’s working past, and the national body the Association for Industrial Archaeology.

Sussex Industrial

Sussex Industrial